While walking along a quiet stretch of beach in the U.S. Virgin Islands a few years ago, Dr. Larry Wood noticed a faint rustle in a pile of dried leaves.

At first, it looked like nothing more than a trick of the wind. But then the leaves shifted again — and something small began to move.

Nestled in the seaside debris was a tiny creature whose brown shell and greenish-gray skin blended almost perfectly with its surroundings. When Dr. Wood leaned closer, his heart leapt.

It was a hawksbill sea turtle hatchling — one of the most critically endangered species on Earth.

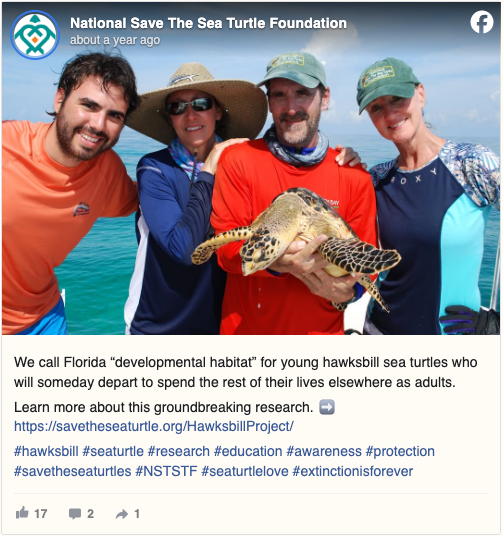

Dr. Wood, who serves as the executive director of the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation, watched as the fragile little turtle stretched its flippers and began its slow crawl toward the ocean.

Against all odds, the baby had survived and was now instinctively making his way home.

At the time, Dr. Wood was participating in a routine nest check survey, working alongside local researchers to monitor sea turtle activity across the islands.

Hawksbill mothers, he explained, are known for nesting high up on the beach, often beneath trees or dense grasses where their eggs can stay cool and hidden.

“Female hawksbill sea turtles typically position their nests high up on the shore, frequently under or among beach vegetation,” the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation shared. “This placement provides natural cover and shelter for the nest.”

Hawksbill turtles are as beautiful as they are important to the ecosystem. With their pointed beaks and vibrant shells, they’re instantly recognizable. But their role in the ocean goes far beyond beauty — they’re spongivores, meaning they feed almost exclusively on sea sponges.

“The digestive systems of adult hawksbills are capable of neutralizing the sharp, glass-like spicules and toxic chemicals found in many sponges,” the foundation wrote. “By eating them, hawksbills prevent sponges from overgrowing and suffocating corals — helping maintain healthy reef ecosystems. A single turtle can consume over 1,000 pounds of sponges every year.”

Sadly, these gentle reef guardians have long faced devastating threats. For centuries, they were hunted for their shells, which were turned into jewelry, ornaments, and combs — part of the global tortoiseshell trade that nearly wiped them out.

“Unfortunately, an estimated 90 percent of the world’s hawksbills were lost to the trade,” Dr. Wood told The Dodo.

Though hunting hawksbills is now illegal, they continue to struggle against pollution, climate change, and habitat loss. But Dr. Wood and other conservationists are determined to change their fate — and he believes ordinary people can help, too.

By refusing tortoiseshell products, reducing plastic waste, supporting coral reef conservation, and protecting nesting beaches, anyone can play a role in giving these turtles a fighting chance.

If everyone does their part, perhaps one day baby hawksbills like the one Dr. Wood found won’t have to struggle just to survive. Instead, they’ll thrive — paddling through clear reefs, grazing on sponges, and living freely in the oceans they call home.

To support their conservation, consider donating to the National Save The Sea Turtle Foundation.