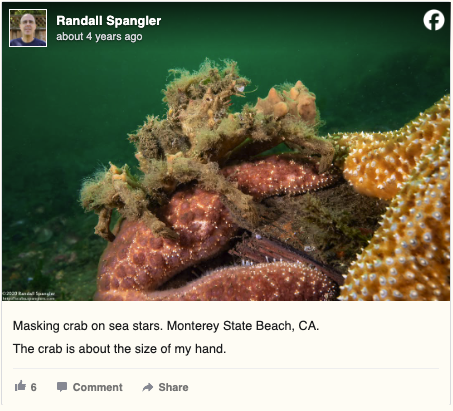

Most sea creatures prefer to stay unburdened, free of anything that might slow them down or get in the way. But not the moss crab. For this quirky crustacean, more is better — especially when it comes to its own camouflage.

Also known as the masking crab, this slow-moving species has an unusual habit: instead of brushing off things that cling to their shells, they actively attach them. The reason? Survival.

“Moss crabs are known for decorating their shells by attaching other organisms such as algae, sponges and bryozoans to their shells, helping them to blend in with their environments,” explains the University of Michigan’s Animal Diversity Web. “The decorated shells of moss crabs act as camouflage, which is important because these crabs move very slowly.”

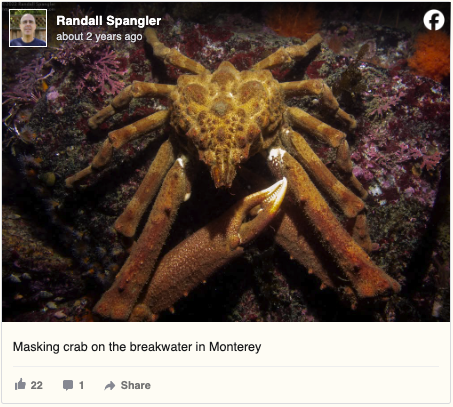

You can see a moss crab here:

But for one diver, the crab’s fashion-forward defense tactic turned into a hilarious underwater surprise.

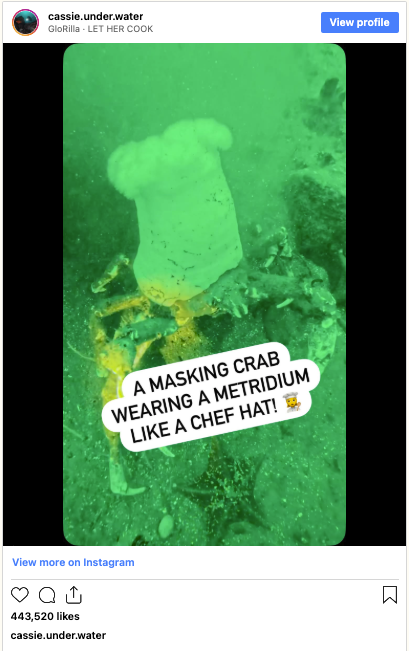

While exploring the ocean last month, scuba diver Cassie Brown came across a moss crab sporting a particularly bold accessory: a large white anemone perched perfectly atop its head.

“Among the more anomalous and HILARIOUS things I’ve seen underwater: a giant masking crab wearing a metridium like a chef’s hat!” Brown shared on Instagram.

Watch that moment here:

Indeed, the anemone resembled an oversized toque blanche — giving the crab the appearance of a tiny underwater chef waddling across the ocean floor.

Though Brown is no stranger to marine life, even she was delighted by the sight. She stayed back to observe the crab in action, marveling at how confidently it moved with its fashionable flair.

The attachment may seem random, but it’s not just luck or glue holding that anemone in place. Moss crabs use microscopic hooked hairs, called setae, to secure their decorations.

Rather than using adhesives, they physically anchor items like algae and small animals to their shells — turning themselves into walking reef real estate.

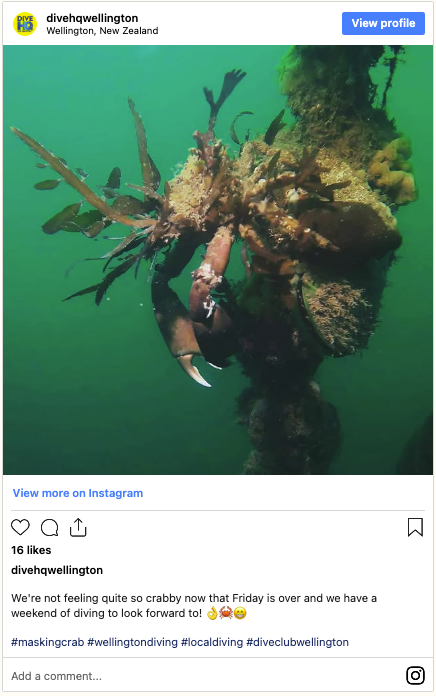

And the relationship benefits both parties. As the crab shuffles along in search of food, the anemone gets a constant flow of water — and often, access to leftovers from the crab’s meals.

“Many of these interactions are symbiotic,” notes marine observer Sanctuary Simon, “with sponges and anemones benefitting from the movement and feeding habits of the crabs they live on.”

So while the crab gets camouflage and distraction, its passengers get prime oceanfront property — a mutually beneficial partnership disguised as comedy.

For Brown, the experience was both amusing and oddly moving — a perfect example of how nature never stops surprising us.

“What a weird and welcome reminder that the ocean owes me nothing but gives me everything,” she wrote.